6.2 Mutation testing

How do we know if we have tested enough?

In the structural testing chapter, we discussed line coverage, branch coverage, and MC/DC. In the model-based testing chapter, we discussed transition coverage and path coverage. All these adequacy criteria measure how much of the program is exercised by the tests we devised.

However, these criteria alone might not be enough to determine the quality of the test cases. In practice, we can exercise large parts of the system, while testing very little.

Consider the following class with a single method:

public class Division {

public static int[] getValues(int a, int b) {

if (b == 0) {

return null;

}

int quotient = a / b;

int remainder = a % b;

return new int[] {quotient, remainder};

}

}

Imagine a tester writing the following test cases:

@Test

public void testGetValues() {

int[] values = Division.getValues(1, 1);

}

@Test

public void testZero() {

int[] values = Division.getValues(1, 0);

}

While these tests give us 100% branch coverage, you probably also noticed that these tests will never fail as there are no assertions!

Fault Detection Capability

Let's discuss one more adequacy criterion: the fault detection capability. It indicates the test's capability to reveal faults in the system under test. The more faults a test can detect or, in other words, the more faults a test fails on, the higher its fault detection capability. Using this criterion, we can indicate the quality of our test suite in a better way than with just the coverage metrics we have so far.

The fault detection capability does not just regard the amount of production code executed, but also the assertions made in the test cases. For a test to be adequate according to this criterion, it has to have a meaningful test oracle (i.e., meaningful assertions).

The fault detection capability, as a test adequacy criterion, is the fundamental idea behind mutation testing. In mutation testing, we change small parts of the code, and check if the tests can find the introduced fault.

In the previous example, we made a test suite that was not adequate in terms of its fault detection capability, because there were no assertions, and so the tests would never find any faults in the code.

Tests with assertions check if the result of the method is what we expect. We have a test oracle now.

@Test

public void testGetValues() {

int[] values = Division.getValues(1, 1);

assertEquals(1, values[0]);

assertEquals(0, values[1]);

}

@Test

public void testZero() {

int[] values = Division.getValues(1, 0);

assertNull(values);

}

To see how the values in a test case influence the fault detection capability, let's create two tests, where the denominator is not 0.

@Test

public void testGetValuesOnes() {

int[] values = Division.getValues(1, 1);

assertEquals(1, values[0]);

assertEquals(0, values[1]);

}

@Test

public void testGetValuesDifferent() {

int[] values = Division.getValues(3, 2);

assertEquals(1, values[0]);

assertEquals(1, values[1]);

}

For the fault detection capability, we want to see if the tests detect any faults in the code.

This means we have to go back to the source code and introduce an error. We replace the division by a multiplication: a clear bug.

public class Division {

public static int[] getValues(int a, int b) {

if (b == 0) {

return null;

}

int quotient = a * b; // the bug was introduced here

int remainder = a % b;

return new int[] {quotient, remainder};

}

}

If we run our tests with the buggy code, we see that the test with the values 1 and 1 (the testGetValuesOnes() test) still passes, but the other test (the testGetValuesDifferent()) fails.

This indicates that the second test has a higher fault detection capability.

Even though both tests exercise the method in the same way and execute the same lines, we see a difference in the fault detection capability.

This is because of the different input values for the method and the different test oracles (assertions) in the tests.

In this case, the input values and test oracle of the testGetValuesDifferent() test can detect the bug better.

Hypotheses for Mutation Testing

The idea of mutation testing is to assess the quality of the test suite. This is done by manipulating bits of the source code and running the tests with this manipulated source code. If we have a good test suite, at least one of the tests will fail on this changed (i.e., buggy) code. Following this procedure, we get a sense of the fault error capability of our test suite.

In mutation testing, we use mutants. Mutants are modified programs which contain the defects, or faults that we introduce in the source code to be then used for determining the quality of the test suite.

A big question regarding the mutants is what their size should be. We can change single operations, whole lines or even multiple lines of code. What would work best?

Mutation testing and the answer to this question are based on the following two hypotheses:

The Competent Programmer Hypothesis (CPH): Here, we assume that the program is written by a competent programmer. More importantly, this means that given a certain specification, the programmer creates a program that is either correct, or it differs from a correct program by a combination of simple errors.

The Coupling Effect: The coupling effect hypothesis states that simple faults are coupled with more complex faults. In other words, test cases that detect simple faults, will also detect complex faults.

Based on these two hypotheses, we can determine the size that the mutants should have. Realistically, following the competent programmer hypothesis, the faults in the actual code will be small. This indicates that the mutants' size should be small as well. Considering the coupling effect, test cases that detect small errors will also be able to detect larger, more complex errors.

Terminology

Before we talk about mutation testing in an in-depth way, we define some terms:

- Mutant: Given a program , a mutant called is obtained by introducing a syntactic change to . A mutant is killed if a test fails when executed with the mutant.

- Syntactic Change: A small change in the code. Such a small change should make the code still valid, i.e., the code can still compile and run.

- Change: A change, or alteration, to the code that mimics typical human mistakes. We will see some examples of these mistakes later.

The example below illustrates mutation testing with these concepts.

Suppose we have a Fraction class with a method invert().

public class Fraction {

private int numerator;

private int denominator;

// ...

public Fraction invert() {

1. if (numerator == 0) {

2. throw new ArithmeticException("...");

}

3. if (numerator == Integer.MIN_VALUE) {

4. throw new ArithmeticException("...");

}

5. if (numerator < 0) {

6. return new Fraction(-denominator, -numerator);

}

7. return new Fraction(denominator, numerator);

}

}

Here is a test suite for this method:

@Test

public void testInvert(){

Fraction f = new Fraction(1, 2);

Fraction result = f.invert();

assertEquals(2, result.getFloat(), 0.00001);

}

@Test

public void testInvertNegative(){

Fraction f = new Fraction(-1, 2);

Fraction result = f.invert();

assertEquals(-2, result.getFloat(), 0.00001);

}

@Test

public void testInvertZero(){

Fraction f = new Fraction(0, 2);

assertThrows(ArithmeticException.class, () -> f.invert());

}

@Test

public void testInvertMinValue(){

int n = Integer.MIN_VALUE;

Fraction f = new Fraction(n, 2);

assertThrows(ArithmeticException.class, () -> f.invert());

}

The test suite contains two tests for corner cases that throw an exception, and two "happy path" tests. We will now determine the quality of our test suite using mutation testing.

First, we have to create a mutant by applying a syntactic change to the original method. Keep in mind that, because of the two hypotheses, we want the syntactic change to be small: one operation/variable should be enough. Moreover, the syntactic change is a change, hence it should mimic mistakes that could be made by a programmer.

For the first mutant we change line 6.

Instead of -numerator we just say numerator.

The mutant looks like as follows:

public class Fraction {

private int numerator;

private int denominator;

// ...

public Fraction invert() {

1. if (numerator == 0) {

2. throw new ArithmeticException("...");

}

3. if (numerator == Integer.MIN_VALUE) {

4. throw new ArithmeticException("...");

}

5. if (numerator < 0) {

// the change was introduced here

6. return new Fraction(-denominator, numerator);

}

7. return new Fraction(denominator, numerator);

}

}

If we execute the test suite on this mutant, the testInvertNegative() test will fail, as result.getFloat() would be positive instead of negative.

Another mistake could be made in line 1.

When we studied boundary analysis, we saw that it is important to test the boundaries due to off-by-one errors.

We can make a syntactic change by introducing such an off-by-one error.

Instead of numerator == 0, in our new mutant we make it numerator == 1:

public class Fraction {

private int numerator;

private int denominator;

// ...

public Fraction invert() {

1. if (numerator == 1) {

2. throw new ArithmeticException("...");

}

3. if (numerator == Integer.MIN_VALUE) {

4. throw new ArithmeticException("...");

}

5. if (numerator < 0) {

6. return new Fraction(-denominator, numerator);

}

7. return new Fraction(denominator, numerator);

}

}

We see that, again, the test suite catches this error.

The test testInvertZero() will fail, as it expects an exception but none is thrown in the mutant. The test testInvert() will also fail since it has a 1 in the numerator which wrongly triggers an exception.

Automation

Writing the mutations of our programs manually might take a lot of time. Moreover, we probably would only think of the cases that are already tested. Like with test execution, we want to automate the mutation process. There are various tools that generate mutants for mutant testing automatically, but they all use the same methodology.

First we need mutation operators.

A mutation operator is a grammatical rule that can be used to introduce a syntactic change.

This means that, if the generator sees a statement in the code that corresponds to the grammatical rule of the operator (e.g., a + b), then the mutation operator specifies how to change this statement with a syntactic change (e.g., turning it into a - b).

We can identify two categories of mutation operators:

- Real fault based operators: Operators that are very similar to defects seen in the past for the same kind of code. Such operators look like common mistakes made by programmers in similar code.

- Language-specific operators: Mutations that are made specifically for a certain programming language. For example, changes related to the inheritance feature we have in Java, or changes regarding pointer manipulations in C.

Most mutation testing tools include various basic mutation operators for real fault based operators. Here are brief descriptions of some common mutation operators:

- AOR - Arithmetic Operator Replacement: Replaces an arithmetic operator by another arithmetic operator. Arithmetic operators are

+,-,*,/,%. - ROR - Relational Operator Replacement: Replaces a relational operator by another relational operator. Relational operators are

<=,>=,!=,==,>,<. - COR - Conditional Operator Replacement: Replaces a conditional operator by another conditional operator. Conditional operators are

&&,||,&,|,!,^. - AOR - Assignment Operator Replacement: Replaces an assignment operator by another assignment operator. Assignment operators include

=,+=,-=,/=. - SVR - Scalar Variable Replacement: Replaces each variable reference by another variable reference that has been declared in the code.

Here are examples for each of the mutation operators with first of all the original code, and then a mutant that could be produced by applying the mutation operator:

Arithmetic Operator Replacement

Original:

int c = a + b;

Mutant example:

int c = a - b;

Relational Operator Replacement

Original:

if (c == 0) {

return -1;

}

Mutant example:

if (c > 0) {

return -1;

}

Conditional Operator Replacement

Original:

if (a == null || a.length == 0) {

return new int[0];

}

Mutant example:

if (a == null && a.length == 0) {

return new int[0];

}

Assignment Operator Replacement

Original:

c = a + b;

Mutant example:

c -= a + b;

Scalar Variable Replacement

Original:

public class Division {

public static int[] getValues(int a, int b) {

if (b == 0 || b == Integer.MIN_VALUE){

return null;

}

int quotient = a / b;

int remainder = a % b;

return new int[] {quotient, remainder};

}

}

Mutant example:

public class Division {

public static int[] getValues(int a, int b) {

if (a == 0 || a == Integer.MIN_VALUE){

return null;

}

int quotient = b / a;

int remainder = quotient % a;

return new int[] {remainder, a};

}

}

In Java, there are a lot of language-specific operators. We can, for example, change the inheritance of the class, remove an overriding method, or change some declaration types. Without going into detail about these language-specific mutant operators, here are some examples:

- Access Modifier Change

- Hiding Variable Deletion

- Hiding Variable Insertion

- Overriding Method Deletion

- Parent Constructor Deletion

- Declaration Type Change

Of course, there are many more mutant operators that are used by mutant generators. For now, you should at least have an idea what mutation operators are, how they work and what we can use them for.

Mutation Analysis and Testing

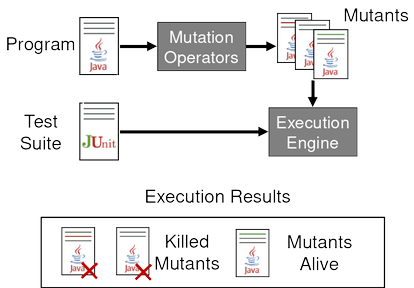

Our goal is to use mutation testing to determine the quality of our test suite. As we saw before, we have to create the mutants first and it is best to do this in an automated way with the help of mutation operators. Then, we run the test suite against each of the mutants with an execution engine. If any test fails when executed against a mutant, we say that the test suite kills the mutant. This is good, because it shows that our test suite has some fault detection capability. If none of the tests fail, the mutant stays alive.

This process is illustrated in the diagram below:

When performing mutation testing, we count the number of mutants our test suite killed and the number of mutants that are still alive. By counting the number of each of these mutant groups, we can give a value to the quality of our test suite.

We define the mutation score as:

Assessing the quality of a test suite by computing its mutation score is called mutation analysis.

Mutation testing then means using this mutation analysis to improve the quality of the test suite by adding and/or changing test cases.

These concepts are highly interconnected. Before mutation testing is carried out, you have to compute the mutation score. This then indicates whether the test suite should be changed. If the mutation score is low, there are a lot of mutants that are not killed by the test suite. You then have to improve the test suite.

Equivalent Mutants

Calculating the mutation score is challenging. The mutation score increases when less mutants are alive. This suggests that the best scenario is to have all the mutants killed by the test suite. While this is indeed the best scenario, it is often unrealistic because some of the mutants may be impossible to kill.

Mutants that cannot be killed are called equivalent mutants. An equivalent mutant is a mutant that always behaves in the same way as the original program. If the mutant behaves like the normal code, it will always give the same output as the original program for any given input. Clearly, this makes this mutant (which is basically the same program as the one under test) impossible to be killed by the tests.

Here, the equivalence is related to the definition of program equivalence. Program equivalence roughly means that two programs are functionally equivalent when they produce the same output for every possible input. This is also the equivalence between the normal code and an equivalent mutant.

Let's have a look at the following method (with some irrelevant parts left out).

public void foo(int a) {

int index = 10;

while (...) {

// ...

index--;

if (index == 0)

break;

}

}

Our mutation testing tool generates the following mutant using relational operator replacement:

public void foo(int a) {

int index = 10;

while (...) {

// ...

index--;

if (index <= 0)

break;

}

}

Note how the original code starts with index set to 10, decrements it at every iteration of the while loop, and breaks out of the loop when index equals 0.

The mutant works exactly the same, even though the condition is technically different.

The index is still decremented from 10 to 0.

Because index will never be negative, the == operator does the same as the <= operator.

The mutant produced by the generator is an equivalent mutant in this case.

Because of these equivalent mutants, we need to change the mutation score formula. We do not want to take the equivalent mutants into account, as there is nothing wrong with the tests when they do not kill these mutants.

The new formula becomes:

For the denominator, we used the number of non-equivalent mutants, instead of the total number of mutants. To compute this new mutation score automatically, we need a way to determine automatically if a mutant is an equivalent mutant. Unfortunately, we cannot do this automatically, as detecting equivalent mutations is an undecidable problem. We can never be sure that a mutant behaves the same as the original program for every possible input.

Application

Mutation testing sounds like a great way to analyse and improve our test suites. However, the question remains whether we can use mutation testing in practice. For example, we can ask ourselves whether a test suite with a higher mutation score actually finds more errors.

A lot of research in software engineering tries to gain some insight into this problem. So far all the studies about mutation testing have shown that mutants can provide a good indication of a test suite's fault detection capability, as long as the mutation operators are carefully selected and the equivalent mutants are removed.

More specifically, a study by Just et al. shows that mutant detection is positively correlated with real fault detection. In other words, the more mutants a test suite detects, the more real faults the test suite can detect as well. Even more interesting is that this correlation is independent of the coverage. Furthermore, the correlation between mutant detection and fault detection is higher than the correlation between statement coverage and fault detection. So, the mutation score provides a better measure for the fault detection capability than the test coverage.

The costs of mutation testing

Mutation testing is not without its costs. We have to generate the mutants, possibly remove the equivalent mutants, and execute the tests with each mutant. This makes mutation testing quite expensive, i.e., it takes a long time to perform.

Assume we want to do some mutation testing. We have:

- A code base with 300 Java classes

- 10 test cases for each class

- Each test case takes 0.2 seconds on average

- The total test execution time is then: seconds (10 minutes)

This execution time is for just the normal code. For the mutation testing, we decide to generate on average 20 mutants per class.

We will have to execute the entire test suite of a class on each of the mutants. Per class, we need seconds. In total, the mutation testing will take seconds, or 3 hours and 20 minutes.

Because of this cost, researchers have tried to find ways to make mutation testing faster for a long time. Based on some observations, they came up with the following heuristics.

The first observation is that a test case can never kill a mutant if it does not cover the statement that changed (also known as the reachability condition). Based on this observation, we only have to run the test cases that cover the changed statement. This reduces the number of test cases to run and, with that, the execution time. Furthermore, once a test case kills a mutant, we do not have to run the other test cases anymore. This is because the test suite needs at least one test case that kills the mutant. The exact number of test cases killing the same mutant does not really matter.

A second observation is that mutants generated by the same operator and inserted at the same location are likely to be coupled with the same type of fault. This means that when we use a certain mutation operator (e.g., Arithmetic Operator Replacement) and we replace the same statement with this mutant operator, we get two mutants that represent the same fault in the code. It is then highly probable that if the test suite kills one of the mutants, it will also kill the others. A heuristic that follows from this observation is to run the test suite against a subset of all the mutants (a technique also known as do fewer). Obviously, when we run the test suite against a smaller number of mutations, the overall testing will take less time. The simplest way of selecting the subset of mutants is by means of random sampling. As the name suggests, we select random mutants to consider. This is a very simple, yet effective way to reduce the execution time.

There are other heuristics to decrease the execution time, like e-selective or cluster mutants and operators, but we will not go into detail about those heuristics here.

Note that, for now, we talked about first-order mutation. Mutants are created by just a single mutation operator. In other words, each mutant contains just a single mistake. However, we can also consider higher-order mutations, where we apply more than a single mutation operator to generate a mutant exists. The idea is that, by combining different mutation operations, we end up with mutants that are harder to be killed.

For interested readers, we suggest the paper Higher Order Mutation Testing by Jia and Harman.

Tools

To perform mutation testing you can use one of many publicly available tools. These tools are often made for specific programming languages. One of the most mature mutation testing tools for Java is called PIT.

PIT can be run from the command line, but it is also integrated into most popular IDEs (like Eclipse or IntelliJ). Project management tools like Maven or Gradle can also be configured to run PIT.

As PIT is a mutation testing tool, it generates the mutants and runs the test suites against these mutants. Then it generates easy to read reports based on the results. In these reports, you can see the line coverage and mutation score per class. Finally, you can also see more detailed results in the source code and check which individual mutants were kept alive. Try it out!

Empirical studies

- Parsai and Demeyer (2020): We demonstrate that mutation coverage reveals additional weaknesses in the test suite compared to branch coverage and that it is able to do so with an acceptable performance overhead during project build.

Exercises

Exercise 1. "Crimes happen in a city. One way for us to know that the police is able to detect these crimes is to simulate crimes and see whether the police is able to detect them."

In the analogy above, we can replace crimes by bugs, city by software, and police by test suite. What should we replace simulate crimes by?

- Mutation testing

- Fuzzing testing

- Search-based software testing

- Combinatorial testing

Exercise 2. Why do we use mutation testing?

- To quickly generate many different test cases

- To test the quality of the test suite

- To find more efficient (refactored) version of methods

- To find sneaky paths in the SUT

Exercise 3. During a board meeting, Alice claims that, due to the test suite written for a software reaching a 98% mutation score, the test suite should be able to catch almost all errors of the SUT. Bob disagrees, claiming that the score merely demonstrates that the test suite can detect simple errors, but not complex ones. Who is (more) correct and why?

Exercise 4. What is not an example of a language-specific operator in Java?

- Changes in lambda functions

- Variable access modifier changes

- Changing

+to- - Removing semicolons

Exercise 5.

Take a look at the method min(int a, final int b, final int c) from org.apache.commons.lang3.math.NumberUtils:

/**

* <p>Gets the minimum of three {@code int} values.</p>

*

* @param a value 1

* @param b value 2

* @param c value 3

* @return the smallest of the values

*/

public static int min(int a, final int b, final int c) {

if (b < a) {

a = b;

}

if (c < a) {

a = c;

}

return a;

}

Which of the following mutation operators can be applied to the method in order to obtain a mutant?

- Arithmetic Operator Replacement (

+,-,*,/,%) - Relational Operator Replacement (

<=,>=,!=,==,>,<) - Conditional Operator Replacement (

&&,||,&,|,!,^) - Assignment Operator Replacement (

=,+=,-=,/=) - Scalar Variable Replacement

Provide an upper-bound estimate for the number of possible mutants of the method above. Assume that our tool replaces every instance of an operator/variable independently.

Exercise 6.

Take a look at the method sum(int[] array) that sums all integers in the array:

public static void sum(int[] array) {

int sum = 0;

for (int i = 0; i < array.length; i++) {

sum += array[i];

}

return sum;

}

Our mutation testing tool created a mutant by replacing i < array.length by i != array.length.

Explain why your, properly written test suite, won't kill this mutant. Will you count this mutant when calculating the mutation score?

Exercise 7. Can the process of determining the mutation score be fully automated and remain accurate? Why or why not?

Exercise 8. Why is it critical to weed out similar mutants?

Exercise 9.

Consider the following class MyMath with the method distanceToInt() and its mutant below:

/**

* <p>Computes the difference between the given number and the nearest whole integer.

* The nearest whole integer can be greater than or less than the input.</p>

*

* @param a value a

* @return the difference between value a and the nearest whole integer.

*/

public class MyMath {

public static double distanceToInt(double a) {

if (a < 0) {

a *= -1;

}

if (a % 1 <= 0.5) {

return a % 1;

} else {

double fractional = a % 1;

return 1 - fractional;

}

}

}

A mutant of distanceToInt():

public static double distanceToInt(double a) {

if (a < 0) {

a /= -1;

}

if (a % 1 < 0.5) {

return a % 1;

} else {

double fractional = a % 1;

return 1 - fractional;

}

}

Which one of the following statements is not correct?

- The mutant is impossible to kill.

- Adding this mutant to the set of mutants when testing will not affect the mutation score.

- The mutant behaves differently from the original program.

- The mutant was created by applying syntactic changes.

Exercise 10.

To test the distanceToInt() method from the previous exercise, a developer writes the following test suite:

@Test

void testDistanceToInt() {

assertEquals(0.3, MyMath.distanceToInt(7.3), 0.00001);

}

@Test

void testDistanceToIntNegative() {

assertEquals(0.1, MyMath.distanceToInt(-4.1), 0.00001);

}

@Test

void testDistanceToIntHalf() {

assertEquals(0.5, MyMath.distanceToInt(2.5), 0.00001);

}

@Test

void testDistanceToIntWhole() {

assertEquals(0, MyMath.distanceToInt(12));

}

@Test

void testDistanceToIntNegativeWhole() {

assertEquals(0, MyMath.distanceToInt(-8));

}

Create a non-equivalent mutant which this test suite would not kill.

Exercise 11. Improve the test suite from the previous exercise to kill the mutant you created.

Exercise 12. Given the mutant from exercise 9, the mutant you created in exercise 10 and the following two mutants, perform mutation analysis by assessing the quality of your improved test suite from exercise 11.

Third mutant:

public static double distanceToInt(double a) {

if (a < 0) {

a %= -1;

}

if (a % 1 <= 0.5) {

return a % 1;

} else {

double fractional = a % 1;

return 1 - fractional;

}

}

Fourth mutant:

public static double distanceToInt(double a) {

if (a < 0) {

a *= -1;

}

if (a % 1 <= 0.5) {

return a % 1;

} else {

double fractional = a + 1;

return 1 - fractional;

}

}

References

- Chapter 16 of the Software Testing and Analysis: Process, Principles, and Techniques. Mauro Pezzè, Michal Young, 1st edition, Wiley, 2007.

- Just, R., Jalali, D., Inozemtseva, L., Ernst, M. D., Holmes, R., & Fraser, G. (2014, November). Are mutants a valid substitute for real faults in software testing?. In Proceedings of the 22nd ACM SIGSOFT International Symposium on Foundations of Software Engineering (pp. 654-665). ACM.